With apologies to Màrius Serra.

15 November 2010

14 November 2010

28 September 2010

What's Wrong with Catalan Schools? (II)

The Catalan school system has three tiers: state/public schools compete directly with publicly funded independent schools, which compete in their turn, more obliquely, with entirely private schools. The independent schools are not authorised to charge tuition, but do.

Three tiers means that greater public funding goes to public schools, from which the greatest uniformity is expected (though some experimentation is allowed). Independent schools are in less of a straight-jacket--for example, single sex schools receive public funding--but share few resources and they do not work as a network. Special programmes are specific to one school, and few schools can have the numbers to set up enriched math, English, or French classes. Consequently, grouping by ability is, like specialisation, almost impossible, and it is left to private schools--and, socially, to the rich--the pursue enriched curricula from which many more students could benefit.

Three tiers means that greater public funding goes to public schools, from which the greatest uniformity is expected (though some experimentation is allowed). Independent schools are in less of a straight-jacket--for example, single sex schools receive public funding--but share few resources and they do not work as a network. Special programmes are specific to one school, and few schools can have the numbers to set up enriched math, English, or French classes. Consequently, grouping by ability is, like specialisation, almost impossible, and it is left to private schools--and, socially, to the rich--the pursue enriched curricula from which many more students could benefit.

12 September 2010

What's Wrong with Catalan Schools? (I)

Stuyvesant High School, founded in lower Manhattan in 1904, has graduated four future Nobel laureates, as well as the Attorney General of the United States. The Bronx High School of Science (1938) boasts seven Nobel-winning alumni, and the Brooklyn Technical High School (1922) two. All three schools are public. None charges tuition. All are selective, basing admission on an entrance examination. All thirteen Nobel prizes were in science or economics. In the same period, seven Nobel prizes have been awarded to Spaniards, five of them to writers. In science, then, three New York City public high schools with a student population of under 11,000 have out-produced a country of over forty million by a factor of six.

There is limited specialisation in Catalan secondary schools, available to students aged 16-18. It is not selective. There are no entrance examinations. Admission to programmes emphasising music and drama entail can be based on auditions, but is otherwise based on across-the-board academic standards. It is not a student applies for admission to university, and thus to a specific major or concentration, that the link between academic merit and the right to walk through a specific set of doors every weekday morning appears.

In publicly funded education, then, students are grouped by area of residence (which often means socio-economic grouping) and in accordance with their parents' religious, linguistics, and ideological preferences. The gifted are not segregated for so much as half a day per week, though legislation requires that they receive special attention, and academic achievement is not rewarded by more challenging work and brighter, more dedicated schoolmates. Elitism is left to the private sector. It shouldn't be.

There is limited specialisation in Catalan secondary schools, available to students aged 16-18. It is not selective. There are no entrance examinations. Admission to programmes emphasising music and drama entail can be based on auditions, but is otherwise based on across-the-board academic standards. It is not a student applies for admission to university, and thus to a specific major or concentration, that the link between academic merit and the right to walk through a specific set of doors every weekday morning appears.

In publicly funded education, then, students are grouped by area of residence (which often means socio-economic grouping) and in accordance with their parents' religious, linguistics, and ideological preferences. The gifted are not segregated for so much as half a day per week, though legislation requires that they receive special attention, and academic achievement is not rewarded by more challenging work and brighter, more dedicated schoolmates. Elitism is left to the private sector. It shouldn't be.

08 September 2010

What's Wrong With This Picture?

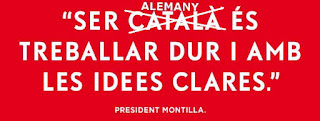

Yesterday Mr Montilla called an election. Today's Vanguardia leads with the election call:

Yet at the end of the op-ed pages, a full colour-illustrated spread sells the speed, safety and toll-free status of the Catalan highway system:

And:

So what's wrong with this picture? On the very day of an election call, with the prospect of voting near, tax money has been spent to tell voters that those governing are good governors and deserve to go on governing, which entails voting for them. There is no cynical asperity, I hope, in pointing out the cynicism of the manoeuvre, the ill service that it does to democracy, the waste, and the imbecile rapacity of the political calculus which it presupposes.

Yet at the end of the op-ed pages, a full colour-illustrated spread sells the speed, safety and toll-free status of the Catalan highway system:

And:

So what's wrong with this picture? On the very day of an election call, with the prospect of voting near, tax money has been spent to tell voters that those governing are good governors and deserve to go on governing, which entails voting for them. There is no cynical asperity, I hope, in pointing out the cynicism of the manoeuvre, the ill service that it does to democracy, the waste, and the imbecile rapacity of the political calculus which it presupposes.

07 September 2010

Bell, California

Might Barcelona be better served by its newspapers than Los Angeles, whose metropolitan area more than doubles that of Barcelona in population? Los Angeles has one metropolitan daily; Barcelona has four. The L.A. Times daily circulation comes to over 600,000, relative to a local population (that of L.A. County) of nearly 10 million. The four Barcelona dailies--La Vanguardia (235,000), El Periódico (180,000), Avui (37,000), and El Punt (30,000)--give Barcelona three quarters the number of daily newspapers in circulation as Los Angeles in absolute terms, relative to a local population of 5.5 million in the province of Barcelona. To the figure for the L.A. Times one would have to add both the L.A. circulation of USA Today and dailies that target smaller markets within the country, such as the L.A. Daily News and La Opinión. Similarly, for Barcelona one would have too add the circulation of a half dozen Madrid dailies which publish Barcelona sections or supplements in their local editions.

This issue suggested itself when, in L.A. County, the Times blew the whistle on city officials in Bell, a municipality of about 36,000 to the south and east of downtown. Like Lester Freamon of The Wire, two Times journalists followed a paper trail: what they found was a +$1.5-million salary, a string of +$400,000 salaries, and a political clique that had been lining its collective pocket as best it could for six years. Obfuscation and loopholes had kept citizens in the dark. A print medium did its job, found the dirt, ran the exposé, and heads--a lot of heads--began to roll. The city is now run by an interim administration.

Perhaps a dozen place names in L.A. County are familiar to movie-goers all over the world. Bell is not among them. Bell is poor, largely Hispanic, and prone to lower voter turnouts: 400 people voted in a plebiscite which gave the now disgraced officials the loophole they needed to circumvent state law and get rich quick. Now that transparency and accountability have returned to Bell, they key question is why they were absent for so long.

The classic source of scrutiny in a liberal democracy is the press. In Bell, it took the press six years to expose the rot. Would it have taken as long in a two-, three- or four-newspaper town? A paper like the L.A. Times is far less reliant on public-sector advertising than one like La Vanguardia, but does that matter if the ratio of print media resources to population shrinks to such an extent that beats are not covered? There's a reason why the final season of The Wire was set in the Baltimore Sun newsroom: newspapers are to democracy what canaries are in a mine. If they die off, the oxygen is going. Even if Spanish papers sometimes read like mouthpieces for political parties of factions thereof, at least they compete, and their investigative resources, if trained on the idealogical enemy, are at least engaged and productive. If public money keeps more papers going, could it be a good thing? Is subsidised Barcelona better off than L.A.?

This issue suggested itself when, in L.A. County, the Times blew the whistle on city officials in Bell, a municipality of about 36,000 to the south and east of downtown. Like Lester Freamon of The Wire, two Times journalists followed a paper trail: what they found was a +$1.5-million salary, a string of +$400,000 salaries, and a political clique that had been lining its collective pocket as best it could for six years. Obfuscation and loopholes had kept citizens in the dark. A print medium did its job, found the dirt, ran the exposé, and heads--a lot of heads--began to roll. The city is now run by an interim administration.

Perhaps a dozen place names in L.A. County are familiar to movie-goers all over the world. Bell is not among them. Bell is poor, largely Hispanic, and prone to lower voter turnouts: 400 people voted in a plebiscite which gave the now disgraced officials the loophole they needed to circumvent state law and get rich quick. Now that transparency and accountability have returned to Bell, they key question is why they were absent for so long.

The classic source of scrutiny in a liberal democracy is the press. In Bell, it took the press six years to expose the rot. Would it have taken as long in a two-, three- or four-newspaper town? A paper like the L.A. Times is far less reliant on public-sector advertising than one like La Vanguardia, but does that matter if the ratio of print media resources to population shrinks to such an extent that beats are not covered? There's a reason why the final season of The Wire was set in the Baltimore Sun newsroom: newspapers are to democracy what canaries are in a mine. If they die off, the oxygen is going. Even if Spanish papers sometimes read like mouthpieces for political parties of factions thereof, at least they compete, and their investigative resources, if trained on the idealogical enemy, are at least engaged and productive. If public money keeps more papers going, could it be a good thing? Is subsidised Barcelona better off than L.A.?

23 August 2010

Politics and Translation

Nothing so frays the tweed, so to speak, of my political convictions as the gratuitous or foolish spending of public funds. Waste feeds the rhetoric of those opposed to the state's corrective role in a free society, as a supplement to the market. For a generation, the epithet "tax and spend" has been used as though it meant tax and waste. Waste taints any policy, however commendable.

Public commemoration of the second Spanish republic, the 1931-1939 Generalitat, the political opposition to Franco and the agents of change during the transition to democracy is such a policy: whether or not it's right for the Catalan authorities to pursue such an objective, or pursue it in the manner in which it is being pursued, there is waste in the programme's budget, though waste most Catalans will never notice.

The waste accompanies an exhibition of very large format photographs of public places, placed in the places they portray. The photographs were taken in Barcelona between 1936 and 1978; they record moments in the political life of the city. Each photographs is accompanied by eight texts: a general introduction to the exhibition (in Catalan, Spanish, English, and French) and a note on the photograph itself (in the same four languages). Here is the introduction, in Catalan:

And in English:

Public commemoration of the second Spanish republic, the 1931-1939 Generalitat, the political opposition to Franco and the agents of change during the transition to democracy is such a policy: whether or not it's right for the Catalan authorities to pursue such an objective, or pursue it in the manner in which it is being pursued, there is waste in the programme's budget, though waste most Catalans will never notice.

The waste accompanies an exhibition of very large format photographs of public places, placed in the places they portray. The photographs were taken in Barcelona between 1936 and 1978; they record moments in the political life of the city. Each photographs is accompanied by eight texts: a general introduction to the exhibition (in Catalan, Spanish, English, and French) and a note on the photograph itself (in the same four languages). Here is the introduction, in Catalan:

And in English:

The translation is poor, but not awful. Now take a look at some of the notes appearing alongside the photographs themselves:

This is so badly garbled that the sense is lost.

Eleven of the twelve photographs have been placed where foreign visitors are most likely to see them: in three central squares, and on a main shopping street. To the visitor with a good command of English, the campaign--and with it, both Catalonia as a polity and as a society (a public campaign is not perceived as a one-off, like a restaurant menu)--conveys either a lack of English language skills, or a lack of concern with the quality of the translations. The translators, who should not be blamed for accepting work while the Spanish economy contracts, are young translation graduates, but not native speakers. The graphic designer, however, is from Liverpool. If he saw the translations, he might have corrected them, or alerted those who had commissioned them that the English texts were sub-standard. Executive responsibility for the exhibition lies with Ricard Martinez, a Barcelona alderman for ERC. If Mr Martinez curates any more exhibitions, he should either save the public money by not commissioning translations, or see to it that the quality of translations is taken as seriously as graphic design.

30 June 2010

9.65, 9.65, 9.65, 9.33

Yesterday's Vanguardia ran profiles of four top-scoring students in June's university access exams, one for each Catalan province. Their marks, out of 10, were 9.65, 9.65, 9.65 and 9.33, and their high school transcripts are likewise stellar. So where will the best and brightest go to school next year? Laura, from Barcelona, will go to law school at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona. Elisabeth, from Olot (seventy miles from Barcelona), will be starting biomed at the Universitat de Barcelona. Juan, from the town of Tarragona, will start Spanish at the Universitat Rovira i Virgili (in Tarragona). It's not clear where Jorge, from Ponts, will study Chemistry. (Apparently he hasn't made up his mind.)

These four students are the top scorers out of over 25,000 who sat the exams. Most university programmes set a pretty low cut-off: 5 is common and I don't know of any over 8. So are these, the best and brightest from Spain's most highly developed economy, headed to Europe's best universities? Or to Spain's best universities? Or abroad? The Pompeu Fabra law school isn't bad, and the U de Barcelona's Faculty of Medicine is among if not the best in Spain, but one wonders if the institutions deserve the students, who have chosen--if that's the word, as the choice is almost made socially before they act--to stay at or very close to home. The best and the brightest could do better.

These four students are the top scorers out of over 25,000 who sat the exams. Most university programmes set a pretty low cut-off: 5 is common and I don't know of any over 8. So are these, the best and brightest from Spain's most highly developed economy, headed to Europe's best universities? Or to Spain's best universities? Or abroad? The Pompeu Fabra law school isn't bad, and the U de Barcelona's Faculty of Medicine is among if not the best in Spain, but one wonders if the institutions deserve the students, who have chosen--if that's the word, as the choice is almost made socially before they act--to stay at or very close to home. The best and the brightest could do better.

16 June 2010

It's Party Time!

Barcelona Mayor Jordi Hereu has an official photo album. The photographs are the work of his press office, some of them clearly posed, and categorised. One appears under a number of headings: it shows the mayor against a backdrop of city buildings, from a Gothic church tower in the middle distance to a Jean Nouvel skyscraper farther back:

The photograph has appeared on the City website and in City publications. It's also in Socialist Party publications, e.g.

The overlap doesn't end there. There's the masthead of the City's monthly bulletin:

And that of the Socialist Party's:

Different, but perhaps not different enough to be different. Here's are two sidebars:

A prize goes to anyone unfamiliar with Catalan who can guess which was published by the City, and which by the Party.

So who paid for the photograph? The City or the party? Or is there--after thirty-two years--some overlap?

The photograph has appeared on the City website and in City publications. It's also in Socialist Party publications, e.g.

The overlap doesn't end there. There's the masthead of the City's monthly bulletin:

And that of the Socialist Party's:

Different, but perhaps not different enough to be different. Here's are two sidebars:

A prize goes to anyone unfamiliar with Catalan who can guess which was published by the City, and which by the Party.

So who paid for the photograph? The City or the party? Or is there--after thirty-two years--some overlap?

13 June 2010

Multi-taskers: Montse Balaguer

Over the last few posts I've been asking if civil society can be bought or simulated. The case I've taken up is that of a plebiscite held in Barcelona in early May. Citizens were given three options on a significant local planning issue: two options were advertised by City Hall and loudly endorsed by a raft of organisations. (See, for example, this op-ed piece in the local edition of the Spanish daily El País.) Turnout was low--under 12%--and 80% of those who bothered to vote opted for the half-hidden third option, that of leaving well enough alone. My example today is that of a civil society aggregator, an umbrella organisation ostensibly speaking on behalf of the whole of third sector in Barcelona: the Consell d'Associacions de Barcelona, or Barcelona Associations' Council.

The CAB is funded by City Hall (in 2009, of 228282 euros of income, 216060 came out of municipal coffers) and housed is a city building. It's hard to gauge real membership, as member organisations are themselves umbrella groups representing smaller associations. All told, the membership list stands at twenty-one, and some of the members are clearly political in orientation.

The CAB's server lodged a website--http://ladiagonal.cab.cat/--which pushed the very message City Hall was pushing in its own pre-plebiscite blanket advertising, though couched in different word. As I mentioned in another post, the CAB signed a manifesto in favour of the very two options favoured by City Hall: of the signatories, four are also members of the CAB, meaning that they signed the manifesto twice.

Montserrat Balaguer i Bruguera, the president of the CAB is--and has been, in a different guise--herself a municipal worker in Mataró, whose governing coalition is led by the same party as is the Barcelona council. She now has a job for life as a "socio-cultural animator".

The association has its own ethical code of conduct, which it recommends to members and to the city's third sector. The code has its own web domain--http://www.codietic.cat--and an office, apparently staffed. (The code's home page is not much more than a news feed, and none of the news has a specifically ethical focus.) The tenth and final item of the summarised code is "an arms-length relationship with government". The CAB echoed its paymaster: the arms invoked must be very short.

The CAB is funded by City Hall (in 2009, of 228282 euros of income, 216060 came out of municipal coffers) and housed is a city building. It's hard to gauge real membership, as member organisations are themselves umbrella groups representing smaller associations. All told, the membership list stands at twenty-one, and some of the members are clearly political in orientation.

The CAB's server lodged a website--http://ladiagonal.cab.cat/--which pushed the very message City Hall was pushing in its own pre-plebiscite blanket advertising, though couched in different word. As I mentioned in another post, the CAB signed a manifesto in favour of the very two options favoured by City Hall: of the signatories, four are also members of the CAB, meaning that they signed the manifesto twice.

Montserrat Balaguer i Bruguera, the president of the CAB is--and has been, in a different guise--herself a municipal worker in Mataró, whose governing coalition is led by the same party as is the Barcelona council. She now has a job for life as a "socio-cultural animator".

The association has its own ethical code of conduct, which it recommends to members and to the city's third sector. The code has its own web domain--http://www.codietic.cat--and an office, apparently staffed. (The code's home page is not much more than a news feed, and none of the news has a specifically ethical focus.) The tenth and final item of the summarised code is "an arms-length relationship with government". The CAB echoed its paymaster: the arms invoked must be very short.

10 June 2010

Multi-taskers: Julio Ríos

One of the civil society organisations backing the City of Barcelona's policy proposals in the recent Barcelona plebiscite was the Federació de Cases Regionals. The cases regionals are social clubs for an older generation of immigrants who'd come to the city from elsewhere in Spain rather than abroad. Their day-to-day business centres on dominoes, dancing, and food.

One of these clubs, the Casa de Ceuta is a modest affair, as befits the modesty of Ceuta itself, a town on seventy thousand inhabitants on the northern African coast, one of two remaining Spanish enclaves. Julio Ríos Gavira presided over the club from 1993 to 2000, when he was elected president of the federation of cases regionals. It's a prominent post, of the kind that can get one a seat beside the Minister of Defence:

Mr Ríos enjoys a seat on the Consell de Ciutat, which is not as its name suggest city council but a consultative body set up to address the democratic deficit by means other than direct election. (Interest groups or functional constituencies are represented on the council, but do not stage internal elections to chose their representative. But that's another story.)

Why did Mr Ríos, on behalf of his federation and its membership, endorse a plan to remodel a major thoroughfare and build a new street car line? Will regional dancers dance down the avenue? Might regional walkers walk down the avenue? Perhaps not: here's a list of municipal grants to cases regionals in 2010, from which I've omitted the object of each grant. Grantees may thus appear more than once:

That's just from one level of government out of eight, and under one heading (that of participation). Why bite the hand that feeds?

Why did Mr Ríos, on behalf of his federation and its membership, endorse a plan to remodel a major thoroughfare and build a new street car line? Will regional dancers dance down the avenue? Might regional walkers walk down the avenue? Perhaps not: here's a list of municipal grants to cases regionals in 2010, from which I've omitted the object of each grant. Grantees may thus appear more than once:

- CASA DE LOS NAVARROS - NAFARREN ETXEA: 1.000,00 €

- CENTRE COMARCAL LLEIDATA: 1.500,00 €

- CASA DE VALENCIA EN BARCELON: 6.000,00 €

- CENTRO ARAGONES DE BARCELONA: 3.700,00 €

- CASA DE CADIZ ASOCIACION ANDALUZA: 1.800,00 €

- CASA DE ALMERIA EN BARCELONA: 2.200,00 €

- CENTRO ASTURIANO DE BARCELONA CULTURA: 2.500,00 €

- CASA DE MENORCA A BARCELONA 600,00 €

- CASA REGIONAL DE MURCIA Y ALBACETE: 2.200,00 €

- CASA DE CEUTA: 3.400,00 €

- CASA DE MADRID EN BARCELONA: 5.200,00 €

- HOGAR EXTREMEÑO DE BARCELONA: 2.500,00

- CASA DE SORIA EN BARCELONA ACTIVIDADES CULTURALES: 2.300,00

- CASA DE CUENCA EN BARCELONA: 2.800,00 €

- CASA DE ANDALUCIA EN BARCELONA: 4.500,00 €

- CENTRO GALEGO DE BARCELONA: 5.100,00 €

- FEDERACION ENTIDADES CULTURALES ANDALUZAS EN CATALUÑA: 5.000,00 €

- FEDERACION ENTIDADES CULTURALES ANDALUZAS EN CATALUÑA: 36.000,00 €

- AMIGOS DA GAITA "TOXOS E XESTAS": 7.500,00 €

- AGRUPACION CULTURAL GALEGA SAUDADE: 8.000,00 €

- FEDERACIÓN DE ENTIDADES SOCIOCULTURALES DE CASTILLA Y LEON: 2.300,00 €

- AMICS DE MALLORCA: 1.100,00 €

- CASA DE CANTABRIA EN BARCELONA: 1.200,00 €

- FEDERACIÓN DE CASAS REGIONALES Y ENTIDADES CULTURALES: 8.000,00 €

- CENTRE ANDALUZ CULTURAL Y ARTISTICO MANUEL DE FALLA: 2.000,00 €

- CENTRE CULTURAL EUSKAL ETXEA: 1.000,00 €

- CASA DE CASTILLA LA MANCHA EN BARCELONA: 2.000,00 €

- FEDERACION ASOCIACIONES EXTREMEÑAS EN CATALUNYA: 4.000,00 €

- HERMANDAD ANDALUZA NTRA.SRA. DEL ROCIO: 4.000,00 €

- FEDERACIO D'ASSOCIACIONS BALEARS A CATALUNYA LES ILLES BALEARS A BARCELONA: 500,00 €

- FEDERACION ANDALUZA DE COMUNIDADES: 1.800,00 €

- CENTRO ARAGONÉS DE SARRIÁ: 2.800,00 €

- CENTRO CULTURAL GARCIA LORCA 9 BARRIOS DE BARCELONA: 1.000,00 €

- CENTRO ANDALUZ DE LA COMARCA DE ESTEPA Y SIERRAS DEL SUR: 500,00 €

- CENTRO LEONES DE CATALUNYA: 3.000,00 €

- FEDERACION DE COMUNIDADES DE CASTILLA LA MANCHA EN CATALUÑA PROJECTE ACTIVITAT: 4.000,00 €

- FEDERACION DE ENTIDADES GALEGAS DE CATALUNYA: 12.000,00 €

- CENTRO ANDALUZ COMARCA DE LINARES: 1.500,00 €

That's just from one level of government out of eight, and under one heading (that of participation). Why bite the hand that feeds?

07 June 2010

Multi-taskers: Carles Martí Jufresa

After the Diagonal plebiscite the mayor of Barcelona, Jordi Hereu, asked for the deputy mayor's head. He got it, close-up included. Or did he? I asked a friend last weekend if Martí had returned to civilian life, à la John Profumo. She laughed. No, she said, he's running the party's next campaign.

His party lists the posts Martí holds:

Diputat/da Provincial

Regidor/a de Benestar Ajuntament de BARCELONA

Regidor/a de Cohesió Territorial Ajuntament de BARCELONA

Regidor/a de President Districte Ajuntament de BARCELONA

Primer/a Secretari/a Federació Barcelona

Conseller/a NacionalOr held, evidently. It seems that Martí is no longer a provincial deputy and he's obviously no longer on city council. He's on the party's payroll rather than the public's, at least in appearance. Parties are publicly funded, so the money's ultimately coming from the same place: he's been moved sideways.We in the West tend to be smug about accountability, as though it were native and original to our cultures. It isn't. It's as old as politics and may erupt into political life informally. Take the reaction of parents in Sichuan Province, China, as their children--in many cases, only children--had died in the May 2008 earthquake because schools had been built below standards. They used the Internet to find the names of officials who should have seen to it that the buildings were properly inspected. Here's what happened to one of the officials:

He got the message: Martí didn't. Expect him to run for the Catalan parliament in the fall.

His party lists the posts Martí holds:

Carles Marti Jufresa

Tinent d'Alcalde Ajuntament de BARCELONADiputat/da Provincial

Regidor/a de Benestar Ajuntament de BARCELONA

Regidor/a de Cohesió Territorial Ajuntament de BARCELONA

Regidor/a de President Districte Ajuntament de BARCELONA

Primer/a Secretari/a Federació Barcelona

Conseller/a NacionalOr held, evidently. It seems that Martí is no longer a provincial deputy and he's obviously no longer on city council. He's on the party's payroll rather than the public's, at least in appearance. Parties are publicly funded, so the money's ultimately coming from the same place: he's been moved sideways.We in the West tend to be smug about accountability, as though it were native and original to our cultures. It isn't. It's as old as politics and may erupt into political life informally. Take the reaction of parents in Sichuan Province, China, as their children--in many cases, only children--had died in the May 2008 earthquake because schools had been built below standards. They used the Internet to find the names of officials who should have seen to it that the buildings were properly inspected. Here's what happened to one of the officials:

He got the message: Martí didn't. Expect him to run for the Catalan parliament in the fall.

02 June 2010

Multi-taskers: Javier García Bonomi

My last post described an instance of the colonisation of civil society by the state on behalf of political parties. In this post, and those to follow, I'd like to examine political actors, the signatories of a manifesto calling upon Barcelona city residents to vote in a plebiscite and vote for either of two out of three options available to voters. I will argue that the signatories are not neutral and the organisations that they represent either not transparent or not representative of civil society.

One of the signatories is the Argentine-born lawyer Javier García Bonomi. Mr. García Bonomi presides over the umbrella organisation for Latin American immigrants in Catalonia Fedelatina, which he founded in 2004. He's on the board of the Taula d'Entitats del Tercer Sector Social de Catalunya (a third-sector platform, set up in 2003), Fundación BABEL: Punto de Encuentro (an NGO doing development work , set up in 2004). the Mesa per la Diversitat en l'Audiovisual (set up to watch over multiculturalism in media regulation in 2005), and sits on a city-wide consultative council in Barcelona, the Consell de Ciutat. He co-hosts the Saturday afternoon radio programme "Communitat" on LatinCOM, a public broadcaster targeting Latin American immigrant listeners.

Is Mr. García Bonomi neutral? Did he act in the interests of his membership in endorsing the plebiscite? More importantly, can he be seen to be neutral? He is a member of the Catalan Socialist party, sitting on two committees which overlap with his mandate at Fedelatina. It's the party that controls the provincial council, which funds LatinCOM; the party that controls Barcelona city council, which staged the plebiscite; and the party that dominates the Catalan Parliament, which controls the Consell de l'Audovisual de Catalunya, which names board members to the the Mesa per la Diversitat en l'Audiovisual. Fedelatina is publicly funded, and not transparently so, as they do not acknowledge the funding that they receive. In a sense, then, García Bonomi the political activist is funding García Bonomi the community activist. Is one of his selves independent of the other? Or is the third sector is really para-public?

One of the signatories is the Argentine-born lawyer Javier García Bonomi. Mr. García Bonomi presides over the umbrella organisation for Latin American immigrants in Catalonia Fedelatina, which he founded in 2004. He's on the board of the Taula d'Entitats del Tercer Sector Social de Catalunya (a third-sector platform, set up in 2003), Fundación BABEL: Punto de Encuentro (an NGO doing development work , set up in 2004). the Mesa per la Diversitat en l'Audiovisual (set up to watch over multiculturalism in media regulation in 2005), and sits on a city-wide consultative council in Barcelona, the Consell de Ciutat. He co-hosts the Saturday afternoon radio programme "Communitat" on LatinCOM, a public broadcaster targeting Latin American immigrant listeners.

Is Mr. García Bonomi neutral? Did he act in the interests of his membership in endorsing the plebiscite? More importantly, can he be seen to be neutral? He is a member of the Catalan Socialist party, sitting on two committees which overlap with his mandate at Fedelatina. It's the party that controls the provincial council, which funds LatinCOM; the party that controls Barcelona city council, which staged the plebiscite; and the party that dominates the Catalan Parliament, which controls the Consell de l'Audovisual de Catalunya, which names board members to the the Mesa per la Diversitat en l'Audiovisual. Fedelatina is publicly funded, and not transparently so, as they do not acknowledge the funding that they receive. In a sense, then, García Bonomi the political activist is funding García Bonomi the community activist. Is one of his selves independent of the other? Or is the third sector is really para-public?

31 May 2010

Grey Corruption

Grey literature is published but seldom indexed, seldom catalogued, and poorly distributed. Grey literature is not noticed. It is at once central and peripheral to the state: central, in that the machinery of government runs on intelligence, which in written form is grey literature; and peripheral in that it is on the fringes of state communication with citizens and the media. Most people have never heard of grey literature, which is very much the point.

Grey corruption is public but seldom investigated, seldom reported, and never prosecuted. Grey corruption is not noticed. I'm going to define grey corruption as the influence of the state on civil society. The example I will take is that of associations. In Catalonia alone there are some 25,000 registered associations, or one for every 280 residents.

Shortly before the Diagonal plebiscite, two groups of civil society organisations stated or demonstrated their support not only for the process but for but two of the three options put forward by the municipal authorities. There was some overlap between these groups. I'll deal with the second group, and the overlap, in my next post. In the meantime, here's a list of the signatories of the "Manifest per a la transformació de la Diagonal" (Manifesto in Support of the Transformation of Diagonal Avenue):

Some of the signatories are para-governmental: No. 9, as its names suggests, is part of the apparatus of municipal administration, headed by an elected politician and governed by a board of whose twenty members ten are named by Barcelona city council. No. 6 is likewise sponsored by city hall, which names four members to a fourteen-member board directly, and another two indirectly. The mayor called the plebiscite, city hall advertised two of the three options; it's no surprise that city hall would support its own initiative.

Of the rest, three related questions suggest themselves. How are they funded? Were they acting independently of political manipulation? And were they exceeding their mandate, concerning themselves with an issue that does not readily mesh with their raisons d'être? A few examples:

I could go on and on, and probably will when I have a chance to trawl for more data. The point is that a civil society will not bite the hand that feeds it: if funding has come from the same funders for over thirty years--if you're tight--you're not likely to act in good faith, independently, with an eye to your own constituency and membership. By way of comparison: if a self-employed professional is only billing one client, isn't that professional an employee of the client's in all but name? If an association is dependent for funding on the largesse of one party through the various levels of government that it controls, how can it be independently and honestly critical?

Then there's the matter of expertise. Civil society is wide and deep. La Leche League and Amnesty International do excellent work, but would we ask for their brief on an urban planning issue? They know about breast-feeding and human rights; they are respected because they stick to what they know. What qualifies Fedelatina or CCOO to issue pronouncements on new designs for a six-lane avenue? Nothing, except the tune being called from the counting house. No wonder half a dozen of the signatories, or constituent organisations, set up polling stations in their offices, though they had publicly campaigned against one of the options.

Grey corruption is public but seldom investigated, seldom reported, and never prosecuted. Grey corruption is not noticed. I'm going to define grey corruption as the influence of the state on civil society. The example I will take is that of associations. In Catalonia alone there are some 25,000 registered associations, or one for every 280 residents.

Shortly before the Diagonal plebiscite, two groups of civil society organisations stated or demonstrated their support not only for the process but for but two of the three options put forward by the municipal authorities. There was some overlap between these groups. I'll deal with the second group, and the overlap, in my next post. In the meantime, here's a list of the signatories of the "Manifest per a la transformació de la Diagonal" (Manifesto in Support of the Transformation of Diagonal Avenue):

- UGT (a trade union federation)

- CCOO (a trade union federation)

- Consell d'Associacions de Barcelona (the Barcelona Associations' Council, not to be confused with the Consell Muncipal d'Associacions de Barcelona or Barcelona Municipal Associations' Council.

- Federació d'Associacions de Veïns i Veines de Barcelona (Federation of Barcelona Neighbourhood Residents' Associations)

- Consell de la Joventut de Barcelona (Barcelona Young People's Council)

- Consell de la Gent Gran de Barcelona (Barcelona Elderly People's Council, which seems not to exist unless it is the same as Consell Assessor de la Gent Gran de Barcelona)

- Diagonal per a Tothom (Diagional Avenue for Everyone, about which more below)

- Fundació Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia

- Institut Muncipal de Persones amb Discapacitat (Muncipal Institute for People with Disabilities)

- Federación de Entidades Latinoamericanes de Cataluña (Federation of Latin-American Organisations of Catalonia)

- Federación de Casas Regionales y Entidades Culturales de Cataluña (Federation of Regional Clubs and Cultural Organisations of Catalonia)

Some of the signatories are para-governmental: No. 9, as its names suggests, is part of the apparatus of municipal administration, headed by an elected politician and governed by a board of whose twenty members ten are named by Barcelona city council. No. 6 is likewise sponsored by city hall, which names four members to a fourteen-member board directly, and another two indirectly. The mayor called the plebiscite, city hall advertised two of the three options; it's no surprise that city hall would support its own initiative.

Of the rest, three related questions suggest themselves. How are they funded? Were they acting independently of political manipulation? And were they exceeding their mandate, concerning themselves with an issue that does not readily mesh with their raisons d'être? A few examples:

- Nos. 1 and 2, the unions, receive state funding, and have enjoyed a great increase in funding under the two successive PSOE minority governments in Madrid. The PSOE's Catalan sister party, the PSC, leads the coalition at city hall.

- No. 4 is an umbrella organisation representing residents' associations large and small all over the city. In the 2010 master list of municipal grants, 128 project grants were made to associations whose titles include the word 'veïns' and which, presumably, belong to the federation. If the average grant were 3000 euros--a low estimate--the total disbursed to member associations would come to 384000 euros.

- No. 5, the Consell de la Joventut, received an 18000-euro generic grant in 2006. It has been an official interlocutor of city hall's on youth policy since 1980 and has signed a series of accords with city authorities since its inception. It runs a youth services centre jointly with the municipal youth services department. For 2010, it was accorded, together with its neighbourhood level constituent bodies, over 5500 euros of municipal funding.

- No. 8, a left-of-centre think-tank, received 18000 in municipal project grants in 2010 and

- No. 10, Fedelatina, was accorded a 27500-euro grant towards the "social integration of immigrated (sic) persons" in March of this year. (The grantor, the Catalan autonomous government, is of the same three political stripes as city hall.) From city hall it's received 32000 euros in project grants, including 10000 for a Latin American Eco-Fest.

I could go on and on, and probably will when I have a chance to trawl for more data. The point is that a civil society will not bite the hand that feeds it: if funding has come from the same funders for over thirty years--if you're tight--you're not likely to act in good faith, independently, with an eye to your own constituency and membership. By way of comparison: if a self-employed professional is only billing one client, isn't that professional an employee of the client's in all but name? If an association is dependent for funding on the largesse of one party through the various levels of government that it controls, how can it be independently and honestly critical?

Then there's the matter of expertise. Civil society is wide and deep. La Leche League and Amnesty International do excellent work, but would we ask for their brief on an urban planning issue? They know about breast-feeding and human rights; they are respected because they stick to what they know. What qualifies Fedelatina or CCOO to issue pronouncements on new designs for a six-lane avenue? Nothing, except the tune being called from the counting house. No wonder half a dozen of the signatories, or constituent organisations, set up polling stations in their offices, though they had publicly campaigned against one of the options.

25 May 2010

Strong Medicine, Weak Doctor

Spain is carrying 225 billion euros of debt that will come due this year. A fund set up to save small savings banks (cajas) caught up in the financial crisis by arranging mergers has just taken charge of Cajasur, and the IMF has called, among other things, for the transformation and de-politicisation of cajas.

Spain has a minority of government. It has had minority governments for thirteen of the last twenty years, and will for the next two. The leader of the opposition, Mariano Rajoy (b. 1955, first elected 1981), does not generally negotiate with the government: he confronts, and his allies in that part of civil society colonised by his party take to the streets and make all the noise they can. Spain cannot afford two more years of confrontation and noise. Mr Rajoy should accept a new role as Mr Zapatero's formal or informal coalition partner, strike deals, defend them, and stick to them. In the absence of a majority government and of any other parliamentary math allowing for stability, ambitious reform depends on it.

Spain has a minority of government. It has had minority governments for thirteen of the last twenty years, and will for the next two. The leader of the opposition, Mariano Rajoy (b. 1955, first elected 1981), does not generally negotiate with the government: he confronts, and his allies in that part of civil society colonised by his party take to the streets and make all the noise they can. Spain cannot afford two more years of confrontation and noise. Mr Rajoy should accept a new role as Mr Zapatero's formal or informal coalition partner, strike deals, defend them, and stick to them. In the absence of a majority government and of any other parliamentary math allowing for stability, ambitious reform depends on it.

21 May 2010

Accounts and Accountability (with apologies to Jane Austen)

Accountability and accounts share seven letters for a reason. Effective democratic governance makes it hard to waste public money, as a corollary, hard to colonise civil society by spreading largesse. Take, for example, an item on page 14 of Thursday's La Vanguardia (click on the clipping for a full view):

There's a bigger story here: where the item was placed in the paper and how long the story will play. Wasting €6 million in public funds isn't an amusing one-off, like a hacker pasting a picture of Mr Bean onto an official web page. The press should report it, public opinion turn against it, and reforms arise from it as a consequence. If waste has no impact on public opinion, no-one will turn off the tap. Thus the mess we are in: public education, universities and health services are under-funded but thoroughly audited and so accountable, while money channelled elsewhere--a.k.a. Fèlix Millet--paid for family outings to the Maldives. If grants make for waste, graft, corruption, and poor accountability, perhaps most of the money granted should be spent by public institutions instead of businesses and the third sector. If you turn on a sprinkler and don't tend your garden, you get weeds. What public spending is Spain needs is the equivalent of drip irrigation.

20 May 2010

Another Referendum: 20 May 1980

Thirty years ago today voters in Québec were called upon to vote on sovereignty. It is one of my earliest political memories, though no-one in my immediate family could vote. The decency of the two principle political actors--Trudeau and Lévesque--is now shocking. For an ounce of retrospect, see http://www.nfb.ca/playlists/champions-series/viewing/champions_part_3/# and start around minute 35.

19 May 2010

Political Ecology

It is a commonplace of Spanish politics that the transition of the late 1970s in unravelling. Here's one reason why: a multi-party system has been superseded in most, but not all, of Spain, by a two-party system. Here's the percentage of votes and number of deputies won by the two winning parties in every election since 1977. Note that the total number of deputies has not varied.

1977: 69.9% (284 deputies)

1979: 65.62% (289 deputies)

1982: 74.8% (309 deputies)

1986: 70.46% (289 deputies)

1989: 65.01% (276 deputies)

1993: 73.66% (300 deputies)

1996: 76.42% (297 deputies)

2000: 78.68% (308 deputies)

2004: 81.6% (312 deputies)

2008: 83.8% (323 deputies)

The institutions set in place in 1978 presupposed a multi-party environment in which deals between big and small parties would be possible and, indeed, desirable. They were to serve as a safeguard against the manipulation of institutions for party-political purposes. In theory, parties would have to seek out honest brokers, independent of party loyalties, for positions in such institutions as the constitutional court. It's the sort of theory that works in a country like Germany.

Elections to the Constitutional Court require a 3/5 majority, i.e. 210 votes, but the winning party in the last election--2008--only holds 169 seats. Only 27 seats are held by other parties (i.e. neither the party in government or the main opposition party). 169+27=196. Spain must now develop an informal mechanism--a culture, as people are fond of saying these days--between the two main parties, or the institution itself will eventually fall apart. When enough justices have died in office or retired, the court won't have a quorum and the whole judicial system will grind to a halt.

I began this post with the observation that most of Spain had adopted a two-party political system. The ecology of parties in the Catalan parliament has trended the other way. Support for the first- and second-place parties began at 50% in 1980, only to jump to 78% (and 113 out of 135 seats). Since then, the percentage of votes going to the two largest parties has declined steadily: in 2006 they only polled 58%.

1977: 69.9% (284 deputies)

1979: 65.62% (289 deputies)

1982: 74.8% (309 deputies)

1986: 70.46% (289 deputies)

1989: 65.01% (276 deputies)

1993: 73.66% (300 deputies)

1996: 76.42% (297 deputies)

2000: 78.68% (308 deputies)

2004: 81.6% (312 deputies)

2008: 83.8% (323 deputies)

The institutions set in place in 1978 presupposed a multi-party environment in which deals between big and small parties would be possible and, indeed, desirable. They were to serve as a safeguard against the manipulation of institutions for party-political purposes. In theory, parties would have to seek out honest brokers, independent of party loyalties, for positions in such institutions as the constitutional court. It's the sort of theory that works in a country like Germany.

Elections to the Constitutional Court require a 3/5 majority, i.e. 210 votes, but the winning party in the last election--2008--only holds 169 seats. Only 27 seats are held by other parties (i.e. neither the party in government or the main opposition party). 169+27=196. Spain must now develop an informal mechanism--a culture, as people are fond of saying these days--between the two main parties, or the institution itself will eventually fall apart. When enough justices have died in office or retired, the court won't have a quorum and the whole judicial system will grind to a halt.

I began this post with the observation that most of Spain had adopted a two-party political system. The ecology of parties in the Catalan parliament has trended the other way. Support for the first- and second-place parties began at 50% in 1980, only to jump to 78% (and 113 out of 135 seats). Since then, the percentage of votes going to the two largest parties has declined steadily: in 2006 they only polled 58%.

18 May 2010

Proliferation

Government has two businesses. It provides services--education, medical care, defence. Citizens use these services, which are tangible in the sense that teachers, doctors, and soldiers can be seen in public places performing their duties. Government also conduct and commission research: in this sense, there is no service other than words spoken at a seminar or symposium or published as a working paper, in a journal, or in a book. In this sense government parallels the work of universities and think tanks; and one of the trends in Spanish government since the transition to democracy has been the founding of publicly funded think tanks, often in tandem with new museums.

How many think tanks is enough? How many is too many? How many can a society afford? It's hard to know. A think tank can do good work, employ useless but well-connected people and do little work, or occupy the middle ground. Some (like Barcelona CIDOB) have built up an impressive international reputation. The European Institute of the Mediterranean (IEMED), a Catalan initiative and, frankly, a vanity project of former Catalan premier Jordi Pujol's, overcame early allegations of nepotism and a series of name changes to make a respectable niche for itself. Like Madrid's Casa de América, a showcase for Latin American countries, the IEMED is now run by a consortium: all three levels of government contribute to the institute's budget. Indeed, the IEMED only needed a name change and an expanded public program to dovetail with Spain's other two casas: Casa África and Casa Asia. Their missions, funding, and models of governance are all broadly similar. One notes in passing that there is also a Casa Árabe, as well as a Casa Sefarad, so few bases had been left uncovered.

How many specifically Mediterranean think tanks can a society afford? Apparently, two. The Casa Mediterráneo, set up in 2009 as yet another vanity project, has a mission that overlaps with the IEMED's. But the IEMED hadn't adopted the 'casa' brand and will remain a think tank. Casa Mediterráneo will be a think tank plus. For the time being, it is of note because the mother of its political godmother, Leire Pajín, is on one of the boards, and because the English of the website is of very poor--if it were a university-level English student, it would fail. If they paid anyone or anything for these translations, they should hang their heads in shame. There has been no quality control whatsoever. Here are a few gems:

"And in this context Casa Mediterráneo has born"

"Casa Mediterráneo throws towards the present and more contemporary world to be a bridge"

"Casa Mediterráneo participates the next 4th March in the Anna Lindh Forum 2010 at Barcelone, a meeting assisted by more than 500 organizations "

"The department Culture and Heritage intends to reveal the contemporary sociocultural realities of the riverside countries through the celebration of activities, by inviting the Mediterranean citizenship and the civil society to know better the cultures involving, mostly unknown."

How many think tanks is enough? How many is too many? How many can a society afford? It's hard to know. A think tank can do good work, employ useless but well-connected people and do little work, or occupy the middle ground. Some (like Barcelona CIDOB) have built up an impressive international reputation. The European Institute of the Mediterranean (IEMED), a Catalan initiative and, frankly, a vanity project of former Catalan premier Jordi Pujol's, overcame early allegations of nepotism and a series of name changes to make a respectable niche for itself. Like Madrid's Casa de América, a showcase for Latin American countries, the IEMED is now run by a consortium: all three levels of government contribute to the institute's budget. Indeed, the IEMED only needed a name change and an expanded public program to dovetail with Spain's other two casas: Casa África and Casa Asia. Their missions, funding, and models of governance are all broadly similar. One notes in passing that there is also a Casa Árabe, as well as a Casa Sefarad, so few bases had been left uncovered.

How many specifically Mediterranean think tanks can a society afford? Apparently, two. The Casa Mediterráneo, set up in 2009 as yet another vanity project, has a mission that overlaps with the IEMED's. But the IEMED hadn't adopted the 'casa' brand and will remain a think tank. Casa Mediterráneo will be a think tank plus. For the time being, it is of note because the mother of its political godmother, Leire Pajín, is on one of the boards, and because the English of the website is of very poor--if it were a university-level English student, it would fail. If they paid anyone or anything for these translations, they should hang their heads in shame. There has been no quality control whatsoever. Here are a few gems:

"And in this context Casa Mediterráneo has born"

"Casa Mediterráneo throws towards the present and more contemporary world to be a bridge"

"Casa Mediterráneo participates the next 4th March in the Anna Lindh Forum 2010 at Barcelone, a meeting assisted by more than 500 organizations "

"The department Culture and Heritage intends to reveal the contemporary sociocultural realities of the riverside countries through the celebration of activities, by inviting the Mediterranean citizenship and the civil society to know better the cultures involving, mostly unknown."

17 May 2010

Underwritten and Undermined

The independence of Amnesty International is founded on funding: Amnesty doesn't accept grants or subsidies of any kind from any public source. International PEN, the world's oldest human rights organisation, is also dependent on its membership and on donors. Writers support writers (and PEN staff, presumably) in their efforts to defend the rights of other writers.

Spanish trade unions, like many of their European counterparts, do not rely on their members: they rely on the State, to the tune of sixteen million euros in 2009. Such generic funding is only part of the picture, as unions qualify for funding under a wide range of programmes for their work in research, training, and development. Yet fewer than one fifth of workers belong to unions, so it's difficult to know whose interests are being defended. Workers lucky enough to have been signed to open-ended contracts (which bind worker and employer until the former's retirement) are difficult and very expensive to dismiss. Other workers may have limited social rights, even in the public sector. I know public university staff who taught for ten years under administrative contracts that did not entitle them to unemployment benefits if they had lost their jobs. Their unions made little noise about the issue and no-one went on strike.

Labour reform would mean stripping the most privileged workers of some of their privileges. Yet, if carried out justly, it would also mean improving the lot of those workers who are, in all but name, second-class citizens. For the time being, the unions have responded to the civil service wage cut by calling for a general strike. The state will be funding a strike against the state as Spain floats on the edge of a maelstrom of insolvency. So be it. What's worth asking is whether public funding of unions has mad them less accountable to workers for the simple reason that they do not need union dues to operate. They are part of the system, paid to play the part they play in collective bargaining and thus make collective agreements possible. Collective bargaining is a right; it is also a necessity for the state, as it simplifies labour law incalculably. When union leaders refer to civil servants whose contracts are iron-clad as "the weakest" members of a society where one worker out of five is unemployed, something other than class interest is at play.

Spanish trade unions, like many of their European counterparts, do not rely on their members: they rely on the State, to the tune of sixteen million euros in 2009. Such generic funding is only part of the picture, as unions qualify for funding under a wide range of programmes for their work in research, training, and development. Yet fewer than one fifth of workers belong to unions, so it's difficult to know whose interests are being defended. Workers lucky enough to have been signed to open-ended contracts (which bind worker and employer until the former's retirement) are difficult and very expensive to dismiss. Other workers may have limited social rights, even in the public sector. I know public university staff who taught for ten years under administrative contracts that did not entitle them to unemployment benefits if they had lost their jobs. Their unions made little noise about the issue and no-one went on strike.

Labour reform would mean stripping the most privileged workers of some of their privileges. Yet, if carried out justly, it would also mean improving the lot of those workers who are, in all but name, second-class citizens. For the time being, the unions have responded to the civil service wage cut by calling for a general strike. The state will be funding a strike against the state as Spain floats on the edge of a maelstrom of insolvency. So be it. What's worth asking is whether public funding of unions has mad them less accountable to workers for the simple reason that they do not need union dues to operate. They are part of the system, paid to play the part they play in collective bargaining and thus make collective agreements possible. Collective bargaining is a right; it is also a necessity for the state, as it simplifies labour law incalculably. When union leaders refer to civil servants whose contracts are iron-clad as "the weakest" members of a society where one worker out of five is unemployed, something other than class interest is at play.

12 May 2010

Trust

Trust is not a feature of arbitrary power. Obedience, coercion, intimidation, indoctrination, and force underwrite the absence of fixed rules, the fluidity of rules. The rule of law means arbiters--judges--and entails trust in those arbiters. As civil society matures, the sources of trust--individuals, groups and institutions who may be relied upon to act independently of state coercion--grow in number and influence, facilitating public scrutiny of the exercise of power.

Whatever trust was generated during Spain's transition to democracy is eroding. Here's proof: Hacienda confirma la financiación ilegal del PP valenciano, que responde con una querella. For those with no Spanish, a political party is suing the revenue service--the tax man--over incriminating documentation. In a country where the revenue service and the judiciary are accused of playing party political games, the rule of law is compromised and democracy under threat.

Whatever trust was generated during Spain's transition to democracy is eroding. Here's proof: Hacienda confirma la financiación ilegal del PP valenciano, que responde con una querella. For those with no Spanish, a political party is suing the revenue service--the tax man--over incriminating documentation. In a country where the revenue service and the judiciary are accused of playing party political games, the rule of law is compromised and democracy under threat.

10 May 2010

"In a democracy, people get the kind of government they deserve"

A bit of counterfactual history: it is 1980, and the Parti Québécois has called a non-binding referendum on Québec's place in or out of the Canadian confederation. Here are the options:

(1) Sovereignty-association (i.e. an independent Québec in a currency union with Canada)

(2) Unencumbered independence (i.e. no currency union)

(3) The status quo

This differs only in one respect from the historical referendum: Option 2 was not on offer. Still, let's imagine that the referendum--which was purely consultative--featured three options, but was conducted under the historical rules. Therefore:

-under the supervision of the chief electoral officer, three committees would have been formed;

-each of the committees would have received equal public funding to conduct its campaign

-total expenditure for each of the committees would have been capped

-equal time for each of the committees would be allotted by broadcaster

-the only other campaign permitted, that of the electoral authorities to explain the purpose and workings of the referendum--that is, the institutional campaign--would have likewise strictly allotted equal space to all three options

The most important outcome of the referendum would have been the same, whatever the number of votes tallied by the three options: the political process was accepted, the vote clean, and the convener--René Lévesque--lost none of the respect he had always received from his political opponents.

This week's Barcelona plebiscite offers none of the guarantees of the 1980 Québec referendum. In response to criticisms that the process was skewed from the outset and money being wasted (it's now clear that €1.3 million was spent on political pantomime, the state disguised as civil society), city hall took out a full page advertisement in Saturday's La Vanguardia, according to which such criticisms are tantamount to "an unacceptable questioning" of the body charged with oversight:

No-one seems to have objected to dissent being labelled "unacceptable". Then again, as Adlai Stevenson is said to have said, "In a democracy, people get the kind of government they deserve."

08 May 2010

Not With a Bang, But a Whimper (Guided Democracy II)

This will be an update to my last post, on the quality of the democratic process in an upcoming referendum on plans to alter the design of one of Barcelona's main cross-city thoroughfares. Last Sunday La Vanguardia published a 20-page special section under its masthead, as part of the paper rather than an insert. It's not clear who paid for it. The lead article is the writer's first professional byline in the paper; the tone is not that of a reporter, but a propagandist. Here, in translation, is an example of that tone, from the opening paragraph:

"The urban renewal of Avinguda Diagonal is not a whim or matter to be taken lightly, but a necessity, for the avenue is polluted, often congested, and falls short of the needs of Barcelona in the twenty-first century."

Voters have three choices in the plebiscite: the third--Option C--is to reject either of the plans for renewal. That option is described as "inmovilista," resistance to change.

Page two of the supplement features an article signed by the mayor; a two-page spread denounces the avenue as "over-crowded" and "agressive"; diagrammes of re-designed intersections are labelled "Option A," "Option B" and "Current Situation," as though Option C were not an option; the back page is a guide to voting.

If this is, as it appear, a publication commissioned by public authorities, it represents the utter decadence of liberal democratic culture in Spain. Information on the formalities of the voting process is mixed with editorialising by a branch of the state which is openly attempting to shape choices to be made by citizens in a public plebiscite, and hiding its own role in making that attempt; and

"The urban renewal of Avinguda Diagonal is not a whim or matter to be taken lightly, but a necessity, for the avenue is polluted, often congested, and falls short of the needs of Barcelona in the twenty-first century."

Voters have three choices in the plebiscite: the third--Option C--is to reject either of the plans for renewal. That option is described as "inmovilista," resistance to change.

Page two of the supplement features an article signed by the mayor; a two-page spread denounces the avenue as "over-crowded" and "agressive"; diagrammes of re-designed intersections are labelled "Option A," "Option B" and "Current Situation," as though Option C were not an option; the back page is a guide to voting.

If this is, as it appear, a publication commissioned by public authorities, it represents the utter decadence of liberal democratic culture in Spain. Information on the formalities of the voting process is mixed with editorialising by a branch of the state which is openly attempting to shape choices to be made by citizens in a public plebiscite, and hiding its own role in making that attempt; and

04 May 2010

Guided Democracy

One of Barcelona's grand avenues is looking a bit shabby and smelling a bit nasty. Avinguda Diagonal, choked by up to eight lanes of traffic, needs a make-over, and the mayor and council have decided to submit the matter to citizens in a non-binding referendum. In a referendum process, as in any electoral process, the state is supposed to be neutral. The state handles logistics; parties and civil society campaign, and citizens vote. Not so in Barcelona: we can vote three ways, but public money is being spent to publicise only two of the options, while the third goes unmentioned or is hushed up. A flashy website (http://www.bcn.cat/diagonal/) does its flash for Option A and Option B; city hall's monthly mass-mailed glosses them; billboards on subway platforms illustrate them. Where is Option C?

City Hall is campaigning, not informing.

The campaign has a Youtube channel (http://www.youtube.com/ideadiagonal#p/a), a Twitter feed (http://twitter.com/IdeaDiagonal), and a blog (http://ideadiagonal.wordpress.com/). The campaign has an official documentary (http://www.bcn.cat/diagonal/46-passat-present-i-futur.html), available for viewing on the self-described "official page of the street". The documentary lacks proper production credits. Who paid for it? Who produced it? I couldn't say. The production values match the quality of the prose on the campaign's web page: they are what you'd expect, derivative, hackneyed, and not very good. Option C must be lost on the editing room floor. Perhaps we'll see it in the director's cut, after we've voted.

29 April 2010

No, We Don't

The Madrid public school authorities have set bilingual programmes in place all over the province. They are advertising the programmes in print media, on television and on the radio, and on public transport. A few examples:

Spanish and foreign media have noticed that the campaign is flogging bad grammar--reinforcing a mistake often made by learners of the English language. Has the campaign been dropped? Corrected? Has anyone apologised or admitted the mistake? No. The English may be bad, say the campaign's defenders, but that doesn't matter: the slogan is effective. Who knows if it is? It's now notorious, at least in Madrid. But the decision to run the ads, once taken, couldn't be reversed. To do so would mean admitting that someone had made a mistake, and no-one in Spain ever makes such an admission about policies or how they are implemented.

25 April 2010

Show Me the Money

A friend who shall go nameless (old joke coming) but whose initials are David Brock (end of old joke) showed me this piece in Saturday's El País. The reporting is not very good. Still, one datum is worth pursuing: CiU paid a direct marketing firm nearly 150,000 euros for mass mailings. (It's not clear when or to how many homes.) A market price for the same service would be about 4000 euros, says El País's Pere Ríos. (His source for the figure or model for reckoning it isn't clear either.) It does seem like a lot of money for a small party. Grants to parties came to over 81 million euros in 2009, of which CiU got less than 2.5 million. If CiU falls into the general pattern of 80% state financing, its total income for 2009 should be about 3.1 million euros, of which the money spent on direct mailing would be 4.8%--a lot for rubbish. But there may be a catch: in election years, most parties are entitled to a per-voter grant which specifically underwrites these kinds of mass mailings, up to 21 euro-cents per voter. There are over 35 million electors in Spain, over 5 million in Catalunya. The latter figure would give CiU over 1 million to spend on mass mailings in a general elections year. Whether that approximates the real cost is another matter. The real issue is this: if parties are funded as though they were state utilities, why are they audited to see that this money is well spent? I haven't found annual reports or auditors' reports on any party web page. What I have found is the logo for a state infrastructure spending stimulus package on the PSOE website (on this page; look for the Plan E logo and link) and the Transparency International index for 2009. Spain is the 32nd most corrupt country on Earth. Not bad, but not good.

20 April 2010

Garzón

Two investigating magistrates (Varela and Marchena), prosecuting another investigating magistrate (Garzón) for misconduct, are being accused of misconduct. That accusation has been levelled in the court of public opinion; formal complaints will follow if Garzón is found innocent.

There are four issues in the Garzón case, and a problem arising from all four. First, the issues:

1) Did Garzón accept payment from a major Spanish bank in return for favours? The bank financed a lecture series at an NYU research centre subsidised by two other bank and Coca-Cola, among others. NYU has issued a statement exonerating Garzón, who had seen identical charges against him dropped twice since 2008. For an account of the charges, see the following piece from last Sunday's Vanguardia:

If after a leave of absence Garzón did not declare a conflict of interest in cases to which the bank was party, the problem may be with conflict of interest guidelines rather than the judge. The investigating magistrate handling the case, Manuel Marchena, has also been busy on the lecture circuit, giving talks at events that have sponsors.

2) Did Garzón knowingly exceed his powers in ordering that conversations between suspects in a political corruption case and their lawyers be taped?

3) Did Garzón knowingly exceed his powers in undertaking his investigation of Civil War-era mass murders? Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have criticised Spain for keeping a 1977 political amnesty law on the books, arguing that it comes into conflict with points of international law from which Spain is not exempt, under its treaty obligations. The UN Human Rights Committee has likewise asked that the 1977 law be repealed.

4) How can it be proven that a public official has knowingly exceeded his or her powers? Garzón is a magistrate working within a complex judicial framework. His actions have not been arbitrary; he believes them to be grounded in points of law. In the ordinary course of court business, disputes over Garzón's actions would be approached as questions of jurisprudence, argued before the judges before whom his cases--those he has investigated--are brought to trial. If the judges do not accept Garzón arguments, out they go, along with the case. Prevarication doesn't mean falling into error: it means knowing that something is wrong and lying about what one knows.

Now, the problem. No-one is debating the fine legal points of the second and third charges against Garzón. No-one understands them. They have been taken for what they do, politically, not for what they say, legally. Lawyer-client privilege is a serious matter; perhaps the law on that point, and so on the wiretaps, is clear, and Garzón did overstep his remit.

The New York Times, The Financial Times and The Economist all smell a fish. The fish is systemic, the unravelling of Spain's post-Franco political settlement. Garzón is regularly referred to by his defenders as a "progressive judge"; in the foreign press he's a "leftist judge". If you let such qualifiers attach to the judiciary with no qualms, justice is partial, and there is no justice. I am reminded, tangentially, of another prosecutor, Archibald Cox. Fired by Nixon over a disputed point of law, Cox did not go down in history not as Nixon's political enemy. "Whether ours shall be a government of laws and not of men," Cox said after his dismissal, "is now for Congress and ultimately the American people to decide." That's the point: the rule or law can exist above politics. Whether or not this is true not matter so much as the belief that it might be true. If you lose that belief, you cease to believe that the game of politics can be played cleanly. Politics has bled into everything in Spain, nothing is clean, and Garzón is no Cox.

10 April 2010

A Programme for Political Reform in Spain

In a democracy, the very existence of a political class is repugnant. The more mature a democracy, the better it will weather a political class's pursuit of its class interests. As Spanish democracy is not mature, it would benefit from formal changes designed to weaken the political class and its structures (e.g. patronage) in favour of more effective scrutiny of public life. Here are my suggestions:

- Abolish the closed-list electoral system.

- Reserve 75% of parliamentary seats for small electoral districts, each sending a single representative to parliament. Use an alternative vote or instant run-off system for voting in these constituencies.

- Reserve 25% of parliamentary seats for open party lists to allow for ideological as well as territorial representation. Restrict anyone winning such a seat from serving more than two terms, unless he or she should run for and win an election in one of the small constituencies.

- Require parties to choose local candidates democratically and locally, i.e. by open election in each electoral district. Restrict voting in such elections to local party members of at least one year's standing.

- Require parties to choose open-list candidates openly and democratically, i.e. by open election among all party members of at least one year's standing.

- Require parties to choose parliamentary leaders and members of the party executive openly and democratically, i.e. by open election among all party members of at least one year's standing. Set fixed terms for such offices.

- Restrict all holders of elected offices from holding any discretionary appointments in the public sector for five years after they leave office. Remove all parliamentary privilege save that protecting holders of elected offices from prosecution for slander or libel for remarks made in an elected assembly. All other protection is either an admission that that the justice system is open to political manipulation or an invitation to break the law.

- In municipalities, institute direct elections for mayor.

- In municipalities where members of the municipal council are paid a full-time salary, restrict the number of council members in accordance with a sliding scale. (Some Catalan municipalities have one full-time councillor per 4500 inhabitants, under a city-wide closed-list electoral system. Over-representation is wasteful, an indirect subsidy for political parties.)

- In municipalities whose population surpasses a set threshold (i.e. 20,000), institute an electoral system of districts or wards for council elections. Under the current system, neighbourhoods have no political voice.

- Determine a fixed and very low percentage limit for the salaries of holders of discretionary posts, in relation to the overall budget for the municipality, autonomous community, or the state itself.

- Remove the principle of parliamentary representation from the governance of public bodies such as public broadcasters and the choice of justices for the Constitutional and other Courts. Party interests are not the public interest. Public appointments commissions, reporting to the ombudsmen (e.g. the defensor/a del pueblo, the sindicatura de greuges), should recommend appointments on the basis of merit after open public competitions.

- Ombudsmen themselves should be chosen by a 75%+1 parliamentary majority vote. If no parliamentary consensus is forthcoming, ombudsmen should be elected directly by popular vote in a special election free from party affiliation.

- Charge the ombudsmen with assessing all public sector advertising and communication. Make it a duty of media outlets to refuse public sector advertising that is not primarily informative and in the public interest. Give the ombudsmen power to fine both advertiser and media outlet if any public-sector advertisement, paid communication or campaign is demonstrably propagandistic.